I am currently a trainee bird ringer, volunteering my time to the British Trust for Ornithology’s ringing scheme. I have been ringing for about 3 years now and absolutely love it! I have expanded my knowledge about birds hugely from having the opportunity to see them up close and look at their plumage and builds in great detail.

Bird ringing is a topic that I get asked about a lot, so I thought I would write a page with a bit more detail about it! If you have any further questions please don’t hesitate to email me at youngnaturalistizzyfry@gmail.com or message me on my social media pages @izzyfryphotography

On my spare weekends when I am not volunteering elsewhere, I am up very early (sometimes as early as 3:30am) in the morning to take part in the British Trust for Ornithology’s bird ringing scheme. The BTO ‘hatched’ the scheme in Britain in 1909, over 100 years ago. Now, over 900,000 birds are ringed in Britain and Ireland each year by over 2,600 trained ringers, most of whom are volunteers

In the early years of the Scheme, it was set out to answer some of the more basic biological questions of the day. Where do our summer visitors spend the winter, and where do our winter visitors breed? In the past, people thought that swallows spent the winter, when they disappeared from Britain, underground in the bottom of ponds! But thanks to ringing we have discredited this myth!

So what is bird ringing? Bird ringing is the attachment of a small uniquely numbered metal ring to the leg of a wild bird that has been stamped with its own number. The rings are super tiny and really light and would feel like us wearing a watch and don’t harm the bird or slow them down in any way and the pliers we put the ring on with don’t hurt them at all either!

The uniquely numbered rings allow individual identification. So for example if the ringed bird is caught again, we can go onto a data base and find out when and where it was ringed. There are lots of different ring sizes, with the smallest, called an AA ring, taken by tiny birds like Chiff Chaffs and Long-tailed Tits, and the largest rings being fitted to Mute Swans.

So how does the process of bird ringing actually work? Bird-ringing involves catching birds, securing a small metal ring around one of their legs, and ideally recording the bird’s species, age, sex, wing length and weight.

Birds are caught in different ways depending on the species. We don’t catch small birds like Robins in the same way that we’d catch a goose! Bird ringers usually use nets to catch birds, but there are also different types of traps that work too.

The most common method of catching birds is a mist net, which looks a bit like a badminton net and is made up of a series of long net pockets strung between two poles. Mist nets are used for catching birds in flight: because the net strings are so thin, birds often don’t see them and fly into the net, falling into one of the pockets. Bird ringers check the nets regularly and carefully extract any birds that have been captured.

Once we have extracted a bird out the net we take it back to our ringing table. The first thing we do is put a ring on the birds leg using special pliers.

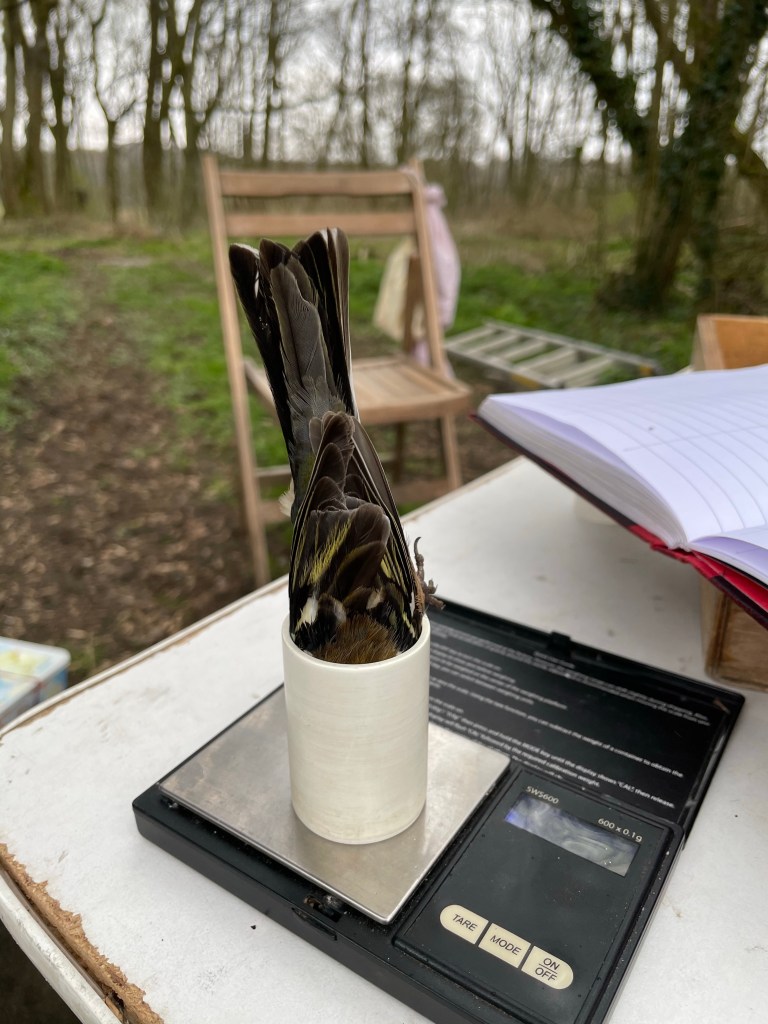

Once we have ringed the bird, the next thing to do is take some measurements. We start by measuring the length of the birds wing with a wing rule. After that we move onto taking a weight measurement. We do this by placing the birds in a little cup on some small scales. We do this to keep the bird calm as its in the dark and also still so we can get an accurate measurement.

We also find out the sex and age of the bird so if its male or female and this is the trickiest part of ringing as its completely different for pretty much every species and that’s why you have to train for 2-3 years to get your license as there’s so many to learn!

So why exactly do we ring birds and spend so much time going through this whole process for each individual?

Well, an important part of wildlife conservation is keeping track of how many animals there are in the wild. This is called population monitoring, and it helps us to identify which species are doing well and which species are declining.

There are lots of different ways to monitor populations, and the method we use depends on the animal group we are interested in. Birds are not always the easiest animals to monitor. They fly, sometimes high in the sky, and they can be secretive and hard to spot in tree canopies and hedgerows. Experts can identify bird species by their songs and calls, and also by the way they are flying. Some people even monitor birds’ nests, recording things like the number of eggs laid and the number of chicks that fledge, providing us with data on breeding productivity. And bird ringing is another method, and this allows us to identify individual birds and helps us to collect all sorts of important data for population monitoring and conservation.

Bird ringing gives us lots of information, such as migration and movements of birds, including where their overwintering sites may be if they are migratory, how long they live for, and whether or not they return to the same breeding site each year.

When we ring birds we can also take some measurements of them. The winglength and weight but we can also do some extra measurements in the summer on migrant birds like seeing how much fat stores they have and the amount of muscle they have. All of the data collected when ringing goes back to the BTO and they then analyse it to make sure populations are ok and to spot any worrying changes.

But when and where do we actually do this ringing?

So a question I always get asked is why do we have to get up so early when bird ringing, and the answer to this is because that is when birds are most active so its when your most likely to catch them! At many sites we try and have the nets up before the sun is even out to maximise how many birds we catch.

Now there are many many groups all of the country which have multiple different sites that they ring at. My ringing group operates over lots of sites of different habitat including woodland, farmland, heathland and chalk grassland all of Wiltshire, Hampshire and Dorset. A few of our main sites include Martin Down Nature Reserve, Bere Marsh Farm Rewildling, Salisbury Plain for raptor boxes and at my family’s farm!

We can also ring pulli which is the term for baby birds in the nest. We usually ring pulli from nest boxes such as tits and raptors but occasionally ring chicks from open nests too. Ringing baby birds is really important as it can tell us about best successes and chick survival and if they are caught later in their lifetime, we can see where they have gone, how far they have dispersed and also how old they are!

Bird ringing is such an incredible conservation tool, and one that I would recommend learning for anyone wanting to go into the ecology or conservation field in terms of a career! This link will teach you how you could become a ringer too: https://www.bto.org/our-science/projects/bird-ringing-scheme/taking-part/learn-ring